A Short Introduction to the Xiangqi Manuals in the Qing Dynasty Part 1

Written by Jim Png of www.xqinenglish.com

Note: This article first appeared on www.xiangqi.com

This article is a continuation of the introduction of the Xiangqi ancient manuals up till the Ming Dynasty. The Qing Dynasty saw a considerable increase in the number of Xiangqi manuals and treatises. Due to the amount of material, the introduction to the ancient manuals written in the Qing Dynasty is divided into two parts.

The contents are as follows:

- Qing Dynasty 1644 – 1912 AD

- Plum Flower Manual

- Strategic Considerations

- Wan Bao Quan Shu

- Remains of the Heart of the Warrior

- Wu Shaolong’s Xiangqi Manual

- Plum Flower Springs Manual

- One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi

- Recluse of the Fragrant Bamboo

- Fathomless Ocean Xiangqi Manual

Qing Dynasty 1644 – 1912 AD

The Qing Dynasty saw a dramatic increase in the number of Xiangqi books being published. Although the majority of the books focused on Xiangqi endgame compositions or problems as would be the term used in International Chess, some books focused on opening theory and whole games. In particular, Wang Zaiyue's Plum Flower Manuals sparked the birth of many more 'Plum Flower Manuals.'

Among the ancient manuals that are still extant, four important ancient manuals were collectively known as the Great Four Xiangqi Manuals of the Qing Dynasty. The first three are:

The Remains of the Heart of the Warrior, One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi, and the Recluse of the Fragrant Bamboo.

As for the fourth manual, Li Geng claims it to be Strategic Considerations, while other different authors and manuals claim it to be Fathomless Ocean.

Plum Flower Manual

《梅花谱》 méi huā pǔ

Author/Editor: Wang Zaiyue (王再越 1662?-1722? wáng zài yuè)

Year: Approximately 60 years after the Secret in the Tangerine, around the same time as Strategic Considerations

Notes: (1 pp. 296-303)

The Elegant Pastime Manual, Secret in the Tangerine, and the Plum Flower Manual are perhaps the three most important ancient manuals in Xiangqi. The publication of the Plum Flower Manual marked the ascension of Xiangqi to another level.

The Elegant Pastime Manual, Secret in the Tangerine, and the Plum Flower Manual are perhaps the three most important ancient manuals in Xiangqi. The publication of the Plum Flower Manual marked the ascension of Xiangqi to another level.

Wang Zaiyue was destitute his entire life, and not much was known about him. Despite his hardships, his work would shape the Xiangqi landscape. Prior to Wang's work, the most played Red opening would be the Central Cannon, and Black would usually counter tit for tat with either the Same Direction Cannons or the Opposite Direction Cannons.

Wang Zaiyue demonstrated that the Screen Horse Defense was a viable counter, if not superior to the Central Cannon. Wang probably never expected that his work would have the influence it has, even today. It 'marked' the end of the era where the Central Cannon seemed to be the only playable option and suggested that the Horse was a viable counter to the Cannon. Wang's work sparked a debate by Xiangqi enthusiasts that is still ongoing called the Cannon-Horse Debate (炮马争雄 pào mǎ zhēng xióng) (1 pp. 296-302)

Like the Invincible Manual, Wang Zaiyue utilized a ninety Chinese character poem where each Chinese character represented a unique intersection on the board.

The ancient manual was divided into two volumes according to extant volumes of the work. There were thirty-one boards with a total of 337 variations. The original or complete name was《梅花必胜谱》 (méi huā bì shèng pǔ) which is to be translated as "Sure to Win Plum Flower Manual." Other than the Screen Horse Defense, there were also boards on the Same Direction Cannons, Opposite Direction Cannons, et cetera.

The level of Xiangqi shown in the Plum Flower Manual was much more sophisticated than the Secret in the Tangerine. Indeed, future generations of Xiangqi enthusiasts would use the Plum Flower Manual as the benchmark to which other manuals were compared. The success of the Plum Flower Annual also sparked a series of ancient manuals that had Plum Flower in their titles, so much so that Wang's edition is considered as the original Plum Flower Manual. The theme of these Plum Flower Manuals was similar. They either demonstrated that the Central Cannon was superior to the Screen Horse Defense, or vice versa.

The author is proud to say that he has translated and published the ancient manual in English.

Strategic Considerations

《韬略元机》 tāo lüè yuán jī

Author/Editor: Wang Xiang (王相 wáng xiàng)

Year: 1707 AD

Notes:

Strategic Considerations consisted of six scrolls. The first four scrolls were endgame compositions (204 boards), while the last two included openings or whole games. There were a total of 46 boards for the last two scrolls. These 46 boards were supposed to have come from the Golden Roc Manual. Like the Elegant Pastime Manual, the endgames were divided into Red-win endgames and endgames that ended in a draw. The majority of the endgames ended in Red winning. Unlike the Elegant Pastime Manual or the Secret in the Tangerine, there were few practical endgames. Instead, most of the endgame compositions were problems.

The level of difficulty of these puzzles was also significantly more challenging than its predecessors. In fact, many Xiangqi scholars use Strategic Considerations to mark the transition of the level of endgames to another level. In the Elegant Pastime Manual and the Secret in the Tangerine, the theme of the puzzles was in Red's favor. Many of these problems demonstrated brilliant Red kills. There was little to no emphasis on defense. However, things changed when Strategic Considerations was published, where Black presented an equally brilliant defense against Red's attack. Instead of problems whereby Red won, Strategic Considerations demonstrated a shift to problems where Black would force a draw. One could consider Strategic Considerations marked the 'death' of the romantic style of play prevalent in the Ming Dynasty.

There were also some exciting counters in Strategic Considerations, namely the Blind Dog Gambit and the Tandem Cannons Defense. There was also significant content concerning the Screen Horse Defense.

There is also a little bit of history to the book title in Chinese. It was originally called 《韬略玄机》 tāo lüè xuán jī. Unfortunately, one of the names of Emperor Kang Xi was 玄烨. To avoid being misinterpreted as being disrespectful, which could have drastic consequences, the title was changed to 《韬略元机》 tāo lüè yuán jī where the third Chinese character was changed to avoid mishap. (2 页 959)

It is considered to be one of the four great Qing Dynasty manuals by modern-day Xiangqi author Li Geng.

Wan Bao Quan Shu

《万宝全书》 wàn bǎo quán shū

Original Author/Editor: Chen Jiru (陈继儒 1558-1639, chén jì rú)

Editor: Mao Huanwen (毛焕文?-? máo huàn wén)

Year: 1739 AD

Notes:

The original book was an encyclopedia, as indicated by "全书." The first two Chinese characters are translated as "ten thousand treasures." Perhaps the title of "Trove of Ten Thousand Treasures would be an apter name. However, the Hanyu Pinyin was used in some Western translations of the book.

The original encyclopedia was written by scholar Chen Jiru who was an acclaimed calligrapher and Chinese painter. He lived toward the end of the Ming Dynasty. Later, Mao Huanwen would add more content and publish it in 1739AD. The author has not been able to find the original text by Chen Jiru and suspects that it is not extant anymore, or this ancient manual should be classified under the Ming Dynasty manual.

Under the segment on Boyi, there were eleven endgame compositions. The first ten had numbers in their titles. The eleven endgame compositions were refinements of puzzles from One Hundred Variations in Xiangqi.

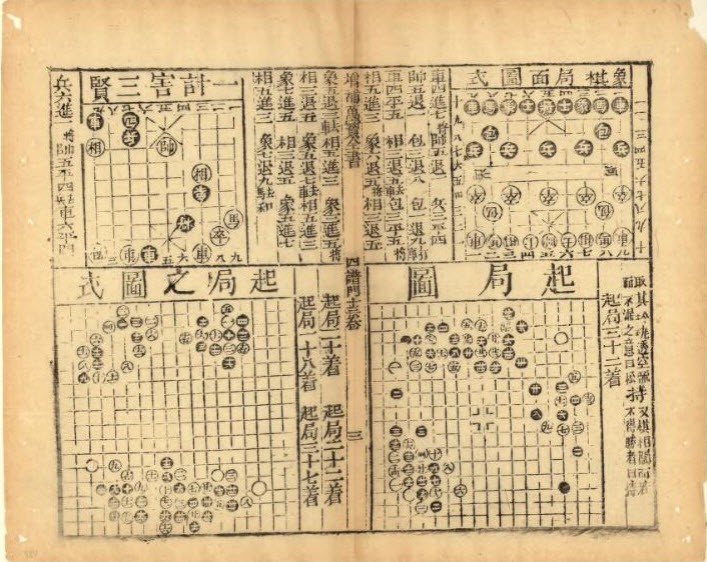

Interestingly, the files were numbered from left to right, as opposed to right to left, which is the norm. See Diagram 1. (3)

Diagram 1 Scroll 12 of Wan Bao Quan Shu showing one of the eleven puzzles (4)

Remains of the Heart of the Warrior

《心武残篇》 xīn wǔ cán piān

Author/Editor: Xue Bing (薛丙 ?-? xuē bǐng)

Year: 1800AD

Notes:

Xue Bing collected problems used by Xiangqi hustlers of his time to make money and edited the puzzles/problems painstakingly into one book. In 1806, Xue Bing would publish the second edition of the book. Xue Bing's contributions to Xiangqi did not end here as he will be mentioned under the section of the Plum Flower Springs Manual.

It is believed that the original book was made up of six scrolls which consisted of one hundred and forty-eight problems. These problems were much more sophisticated than their predecessors, and most of the problems ended in draws.

According to Professor Zhang Ru-an, the Heart of the Warrior was significant because it was the first book to mention the rules of Xiangqi used in ancient times. The rules have since changed significantly since ancient times, which is why some of the ways of attacking were allowed in the same problem in ancient times. The same moves would be considered to have gone against the rules of modern times.

There was also advice on how to play the endgame.

The Remains of the Heart of the Warrior was an essential ancient manual and regarded as one of the great four Qing Dynasty Xiangqi manuals.

Wu Shaolong’s Xiangqi Manual

《吴绍龙象棋谱》 Wú shào lóng xiàng qí pǔ

Author/Editor: Wu Shaolong (吴绍龙, ?-? Wú shào lóng)

Year: Slightly after the publication Heart of the Warrior (1800 AD?)

Notes:

This ancient manual was unique as it was one of two ancient manuals that contained actual games played. Xiangqi scholars have used it to gauge the level of play in the Qing Dynasty.

Not much else is known about the author or the book except that it was mentioned in the preface that the author had read the Heart of the Warrior. He was also believed to have been a Xiangqi expert of his time, so Xue Bing asked him to proofread his book.

It is believed that there were records of twenty-six games that Wu played. Unfortunately, only sixteen games remained. Wu took Black in fourteen of the sixteen games and gave up two moves in one of the handicap matches. An interesting point to note was that the Pawn Opening was used in ten of the matches. The Pawn Opening was not considered to be mainstream at that time. The remaining six matches were Central Cannon vs. Screen Horse Defense matches.

Plum Flower Springs Manual

《梅花泉》 méi huā quán

Original Author: Tong Shenggong (童圣公tóng shèng gōng)

Improved: Xue Bing (薛丙 ?-?, xuē bǐng)

Year: Jiaqing era 1796-1820AD

Notes: (1 pp. 348-353)

Tong Shenggong was the author of the original manual. Not much is known about him. In the original version, there were 36 boards with 136 variations.

Tong Shenggong was the author of the original manual. Not much is known about him. In the original version, there were 36 boards with 136 variations.

Later, Xue Bing would study and make improvements to Tong's work. He expanded the work to 50 boards with over 200 variations.

The Plum Flower Springs Manual demonstrated several 'new' opening systems and variations of its time, like the Central Cannon vs. Mandarin Duck Cannons, the Left Single Horse Defense, the Left Tandem Cannons, et cetera. Perhaps the most remarkable was the Horse Gambit to trap Chariot Variation, which is still a commonly seen variation in modern times.

There were three volumes to the work.

Volume 1 (上卷): 13 Boards which ended in draws.

Volume 2 (中卷): 14 Boards where the initiative would be won

Volume 3 (下卷): Non-extant. It was supposed that there were 21 boards that discussed various handicap situations.

This ancient manual has been listed after Remains of the Heart of the Warrior as Xue Bing finished that book before expanding Tong Shenggong's original work. Xue Bing's contributions must be mentioned here.

During Xue Bing's time, Xiangqi activity was bustling, but most of the players were only interested in creating problems. Opening theory stalled. Professor Zhang Ru-an said that Xue Bing's work filled the void during that time.

The author is proud to announce that he has published the book in English.

One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi

《百局象棋谱》 bǎi jú xiàng qí pǔ

Author/Editor: San Le Ju Shi (三乐居士 sān lè/yuè jū shì)

Year: 1801 AD (earliest version)

Notes:

One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi was another very influential ancient manual. It was initially published in 1801AD. The author has translated the name to be San Le Ju Shi, where the second Chinese character could also be read as 'yue.' The author's identity cannot be ascertained. 居士 is a Buddhist term that can be used to refer to several different people. The Wikipedia translation is householder, which the author does not agree with but cannot find a better translation.

Eight scrolls were divided into four volumes, and the ancient manual contained 106 Xiangqi problems. There was a board that was repeated. Most of the boards ended in draws, and there similar tactical themes. From the names of the problems, which were considered rather uncouth, it is believed that the problems were the same problems that were used by street hustlers.

One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi is not to be mistaken with One Hundred Variations of Xiangqi. The complexity of the problems given in the book was remarkable for its time, and the book was very popular in its time. Indeed, it was perhaps the most commonly used book by Xiangqi hustlers for decades up till the twentieth century. Many other ancient manuals contained the material found in One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi.

It is considered to be one of the four great Qing Dynasty manuals.

Please be reminded that One Hundred Boards of Xiangqi and One Hundred Variations of Xiangqi are two different manuals.

Recluse of the Fragrant Bamboo

《竹香斋象棋谱》 zhú xiāng zhāi xiàng qí pǔ

Author/Editor: Zhang Qiaodong (张乔栋 ?-1812AD, zhāng qiáo dòng)

Year: 1804AD

Notes:

The Recluse of the Fragrant Bamboo is considered to be one of the four great Qing Dynasty manuals. It is also the last of the Great Four Xiangqi Manuals of the Qing Dynasty. It is considered to be the culmination of the study into problems during the Qing Dynasty.

The editor was Zhang Qiaodong, who had a small plot of land behind his house. He built a small enclosure which he called the Recluse of the Fragrant Bamboo. In this small enclosure, he invited fellow Xiangqi enthusiasts to come over and analyze various puzzles. Together they discovered mistakes in the problems and proceeded to improve upon them. The collective efforts of Zhao Qiaodong and his friends culminated in the ancient manual, which was named after their meeting place. Not much else is known about Zhang Qiaodong.

There were two versions of the ancient manual. In the 1804AD version, there were three volumes which contained 84 boards, 76 boards, and 48 boards, respectively

The second version was published in 1817 AD. There were also three volumes which contained 78 boards (divided into two scrolls), 70 boards (divided into two scrolls), and 48 boards (divided into four scrolls).

The vast majority of the problems ended in draws, and the third volume contained the most demanding problems.

Diagram 2 Photo Credit to Rick Knowlton

Fathomless Ocean Xiangqi Manual

《渊深海阔象棋谱》 yuan shēn hǎi kuò xiàng qí pǔ

Author/Editor: Chen Wenqian (陈文乾 chén wén qián)

Year: 1808 AD

Notes:

According to the preface written in the ancient manual, it took seventeen years for Chen Wenqian to collect various endgame problems of his time. He spent time studying the problems, found inadequacies, and made improvements. Several endgame compositions were Chen's creations, and they were marked with the Chinese character '新,' which means 'new' in Chinese.

Fathomless Ocean has been considered to be one of the great four Xiangqi manuals on problems from the Qing Dynasty.

References

1. 张, 如安. 中国象棋史. 北京 : 团结出版社, 1998. 7-80130-170-6.

2. 程明松, 杨明忠 和 屠景明. 中国象棋谱大全. 成都 : 成都时代出版社, 2007 重印. 页 1788. 9787805485294.

3. 陈继儒(晚明). Wan Bao Quan Shu 万宝全书. [编辑] (清)毛焕文. 卷 12.

4. (清)毛焕文. 增补万宝全书. 1739. 卷 12.