Origins of Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) 04: Western Zhou Period and Bo

In the previous article, after King Wu of Zhou defeated King Zhou of Shang, the Zhou Dynasty was formed and was the longest dynasty in China's history. The history of the Zhou Dynasty is very complicated and is divided into three sections for discussion. Regarding the origins of Xiangqi, the earliest mention of one of the ancient prototypes of Xiangqi, Bo, occurred during the Western Zhou Dynasty.

- Hypothesis number 5: Liubo was the precursor of Xiangqi

Liubo was an ancient game that was characterized as one of the games of Bo. How Liubo is played and the relevant ancient passages will be discussed in several articles. The topic of the Games of Bo and its origins will be discussed here.

Liubo was an ancient game that was characterized as one of the games of Bo. How Liubo is played and the relevant ancient passages will be discussed in several articles. The topic of the Games of Bo and its origins will be discussed here.

Liubo was an ancient game that was characterized as one of the games of Bo. How Liubo is played and the relevant ancient passages will be discussed in several articles. The topic of the Games of Bo and its origins will be discussed here.

- Hypothesis number 6: Board games had their origin in divination ceremonies

Hypothesis number 6 was put forward by Professor Joseph Needham and will be discussed in a later subsection. It would be sufficient to know that the I Ching, or the Book of Changes was believed to have been written during the Western Zhou Period.

- Some background history

- King Mu of Zhou played Bo against Jing Gong: Earliest Written Record of Bo

- Earliest historical mention of Bo

- Bo is also mentioned in the Records of the Grand Historian

- Other cited inventors of Bo?

- Some inferences on Bo

- Confusion with the etymology of Bo 博

- Boyi baffling the early Western Historians

- Divination and the origins of Chess

- A final noted about the Western Zhou

- References

Some background history

Short background history is required to put things in perspective.

The Zhou Dynasty was formed in c. 1046 BC after King Wu of Zhou overthrew the last king of Shang, King Zhou of Shang.

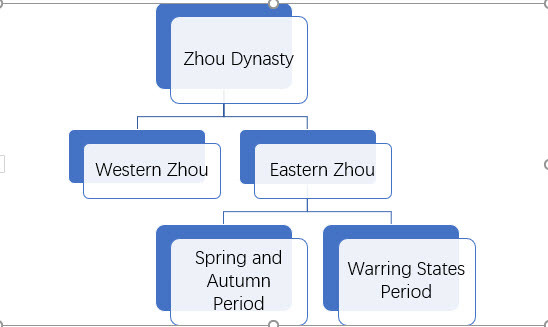

While the Zhou Dynasty, spanning from c. 1046 to c 221 BC, has been the longest dynasty in China's history; the empire had effectively lost power by around 770 BC. The empire was fragmented into dozens of states vying for power. Historians would describe this Period as the Spring and Autumn Period 春秋时代 (Chūn-Qiū Shí dài). Later, some of the smaller states would join forces until there were main warring states, which marked the beginning of the Period of the Warring States 战国时代 (Zhàn guó Shí dài). Eventually, the Warring States ended after the State of Qin conquered all the other states to establish the Qin Dynasty, which was the first time in history that China was unified.

The history of the Zhou Dynasty has been divided into three periods for study:

- Western Zhou (c. 1045- c. 771 BC),

- Spring and Autumn Period (c. 771 – 476 BC), and

- Warring States Period (c. 476 – 221 BC).

This article would only discuss events related to the origins of Xiangqi that happened during the Western Zhou Period. The Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, collectively referred to as the Eastern Zhou, will be subsequently discussed in later articles.

This Period in the history of Xiangqi is remarkable because of the games of Bo, especially Liubo, which some Chinese historians and scholars believe to be the 'ancestor' of Xiangqi.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

King Mu of Zhou played Bo against Jing Gong: Earliest Written Record of Bo

There was more mention of Bo in the tenth century BC.

King Mu of Zhou (周穆王滿 zhōu mù wáng mǎn c. 992 BC- 922BC) was the fifth king of the Zhou Dynasty. He was also believed to have been an avid fan of Liubo. (1)

There is a passage in a very ancient novel Mu Tian Zi Zhuan (《穆天子傳》 mù zǐ tiān zhuàn) that is still extant which mentioned King Mu of Zhou playing Bo. When the novel was written is not known, but it was believed to have been written during the Period of the Warring States (c. 475-221BC). King Mu of Zhou was the leading character in the novel. The novel was perhaps the earliest mention of Bo. While there were other mentions of Bo in the ancient texts like the Records of the Grand Historian, the mention of Bo in Mu Tian Zi Zhuan is the earliest to date. The Records of the Grand Historian was written centuries later. (2)

The novel has been translated as The Story of Mu the Emperor in the author's earlier work. The novel has also been translated as Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven in various websites and literature. (3)

In the novel, there were TWO instances of him playing Liubo against Jing Gong (井公jǐng gōng), who was believed to be a wise hermit that King Mu of Zhou met during his travels. (4 p. 3)

《穆天子传》卷五:“是日也,天子北入于 邴 ,与 井公 博,三日而决。”

《穆天子传》卷五:“戊寅,天子西升于阳。□过于灵□井公博。”

(5) (6)

The '□' was used as a spacer to indicate that some words could not be made out.

It is beyond the author's translative abilities to translate the passage as they contained geographical places that are not very clear even today. The key phrases would be "与 井公 博,三日而决" which would mean that King Mu of Zhou played Liubo with Jing Gong for three days. Their second encounter would be '井公博,' which would mean that they played Liubo again. The two passages were found in the same chapter.

King Mu of Zhou playing Bo has been mentioned by many Chinese historians, including Li Songfu, who stated that later poems would sometimes describe deities playing Liubo. As the novel was supposed to have been written during the Period of the Warring States, it would suggest that Bo had already been in existence and even popular or well-known as the king had also played it. (7)

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Earliest historical mention of Bo

In Shuo Wen Jie Zi (《说文解字》,Shuō wén Jiě zì, abbreviated as 《说文》), the dictionary by Eastern Han scholar Xu Shen (许慎 Xǔ Shèn), mentioned under the entry on Bo:

"Bo: A board game. Six Zhu and twelve Qi. Pronounced as Bo. Wu Zhou of the ancient times invented Bo."

《说文解字。卷六。竹部》簙:局戏也。六箸十二棊也。从竹博声。古者乌胄(zhòu)作簙。

Shuo Wen Jie Zi was written in 100AD and was published in 121AD. (8)

Wu Zhou would also be Wu Cao in this case as it was another name of his.

Wu Cao was believed to be a minister serving King Jie of Xia, the last ruler of the Xia Dynasty. King Jie of Xia was reported to have ruled around 1654-1600BC (some sources suggest 1725-1675BC), where his rule as a tyrant was brought down by Tang of Shang (商汤 Shāng Tāng), thus ushering in the Shang Dynasty. Wu Cao was also believed to have invented the brick. (9) (10)

The description of Bo given in Shuo Wen Jie Zi referred to the ancient game Liubo. Liubo is believed by many Chinese scholars to have been the proto-chess from which Xiangqi was derived.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Bo is also mentioned in the Records of the Grand Historian

As mentioned above, the Records of the Grand Historian had also mention of Bo.

As mentioned above, the Records of the Grand Historian had also mention of Bo.

Records of the Grand Historian, Annals of Yin:

"The Emperor Wuyi was unprincipled and made images, which he called 'Heavenly gods.' With these he played chess, ordering someone to make the moves for them; and when the 'celestial gods' did not win he abused them, and making a leather bag, filled it with blood, threw it up and shot at it. This he called shooting at Heaven. While Wuyi was hunting between the Yellow and Wei rivers, there was a clap of thunder, and Wuyi was struck dead by lightning."

《史记.殷本纪》

帝武乙无道,为偶人,谓之天神。与之博,令人为行。天神不胜,乃僇辱之。为革囊,盛血,卬而射之,命曰 "射天" 。武乙猎于河渭之闲,暴雷,武乙震死。子帝太丁立。帝太丁崩,子帝乙立。帝乙立,殷益衰。 (11)

'Emperor Wuyi' has also been translated as King Wu of Shang (武乙 wǔ yǐ, ? – c. 1112 BC). (12)

The Records of the Grand Historian was written by Sima Qian and was finished around 94BC and remains the definitive text on history before the Han Dynasty. (13)

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Other cited inventors of Bo?

Bo was also cited for having been invented by King Zhou of Shang! King Zhou of Shang has been mentioned in the previous article in the section.

In the

(宋)李昉

《钦定四库全书。太平御览卷七百五十三。工艺部十五。围碁》

又曰陶侃在荆州见佐吏博弈戏具投之于江曰围碁者尧舜以敎愚子博者商纣所造诸君并懐国器何以为此 一本为牧猪奴戏 (14)

In the Tai Ping Yu Lan Scroll 753, on the Fifteen Chapter on Gong Yi and the topic discussing Weiqi, it was written that Weiqi was invented either by Yao or Shun (the ancient emperors mentioned in the earlier article). The relevant passage was "围碁者尧舜以敎愚子." Bo was invented by King Zhou of Shang (博者商纣所造 bó zhě shāng zhòu suǒ zào).

The version of the Taiping Yulan (15) that the Webmaster has found was collected in the Siku Quanshu. The Taiping Yulan was a massive Chinese encyclopedia compiled under Li Fang from 977-983 AD during the Song Dynasty. It is divided into 1000 volumes and 55 sections, which consisted of about 4.7 million Chinese characters.

The Siku Quanshu was a very ambitious undertaking to collect all the ancient works into one big volume during the Qing Dynasty. (16)

Note: The Taiping Yulan would seem to be a key book that might have caused misunderstanding in the early Western historians regarding the origins of Xiangqi. This topic would be discussed later on.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Some inferences on Bo

Although different sources cited different inventors of Bo, we can safely assume that the game was well-known by the Zhou Dynasty. And it could have well been played even earlier during the Shang Dynasty, as suggested by the inventors being Wu Cao or King Zhou of Shang.

While only Shuo Wen Jie Zi 'defined' the game as Liubo, the passage in the Records of the Grand Historian and the Taiping Yulan DID NOT specify what kind of game Bo was referred to.

Later passages from Shuo Yuan would seem to match the description of Liubo as suggested by Shuo Wen Jie Zi, and that is why some historians have suggested that Bo was, in fact, Liubo.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Confusion with the etymology of Bo 博

The etymology of Boyi (博弈 bó yì) has been most confusing.

The etymology of Boyi (博弈 bó yì) has been most confusing.

As mentioned in Shuo Wen Jie Zi above, the definition given for Bo was simply Liubo.

Yi, '弈,' would later refer to Weiqi in ancient times as a noun. The same Chinese word would also refer to the act of playing chess (generic term).

But were there any other games of Bo? YES.

In Zhang Ru-an's book, he devoted the first chapter to the various games of Bo. These games included Liubo, Sai, Tanqi, and Prasaka. (4) And these games were suggested by him to have been related to Xiangqi.

In a dissertation by modern-day Taiwanese scholar Chen Jiahong on the topic of the culture of Boyi in the Song Dynasty, the list had expanded to over ten games which were divided into three categories for discussion (17 pp. 21-22):

- Games of Pure Luck

- Games that required a combination of luck and skill (notable were Prasaka/Shuang Lu and Hitting the Horse, which was mentioned in the poetess Li Qingzhao's description)

- Games of Pure Skill (which includes Xiangqi and Weiqi)

The games listed here had taken on a gambling nature. Indeed, Liubo was played with dice. Liubo or Sai or Tanqi was NOT MENTIONED in Chen Jiahong's dissertation because he was writing about Boyi in the Song Dynasty. Liubo, Sai, and Tanqi had already fallen out of favor by then.

Boyi has also been associated with gambling. The Chinese for gambling is 赌博 (dǔ bó), but the term itself was invented centuries later.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Boyi baffling the early Western Historians

The identity of Boyi also sparked some interest in a few of the early Western historians. However, it would seem that they were limited in resources and could only have a vague idea. And only a few historians bothered to examine Boyi.

K. Himly stated:

"The etymology of the two words po and yi is as obscure as our notions about the customs and pastimes of so remote an antiquity must necessarily be, so we can only state what are their accepted meanings now. " (18 p. 106)

Note: K. Himly used po instead of bo. Po would be Wade-Giles romanization, which was popular in his time.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

Divination and the origins of Chess

As mentioned earlier:

- Hypothesis number 6: Board games had their origin in divination ceremonies

About Xiangqi and divination, the Oxford’s Companion to Chess had this to say:

“For the last hundred years, the view has been developing that board games had their origin in divination ceremonies. Professor Needham, the Sinologist, believes that a quasi-astrological technique which evolved in China between the 1st and 6th centuries AD for determining the balance between the Yin and Yang was converted to military divination purposes in India or China and probably formed the basis of Chaturanga. By controlling the fall of objects on to a divination board, the gods could communicate with men. At a later stage, dice were added to determine the moves of the pieces and further reveal the celestial mind. Then someone was sacrilegious enough to convert this process to a game, perhaps eliminating the dice. The person who secularized the religious process has, perhaps, the best claim to be the ‘inventor’ of chess.”

(19 p. 144)

The author did some research and managed to find the actual passage that Joseph Needham had written in Science and Civilization in China.

“… In any case, the important thing to notice is that in China, and in China alone, on account of the dominance of the Yin-Yang theory of the macrocosm, could a divination technique or ‘pre-game’ have been devised which was both astrological and yet had a sufficient combat element to enable it to be vulgarized into a purely military symbolism….”

(20 p. 324)

There remains much research to be done for this hypothesis, but it would be important to know that the I Ching (易經Yìjīng), or Book of Changes as it has been translated, was written during the Western Zhou. It is among the oldest of the Chinese classics that is still very influential even today. It was originally a divination manual and has served as guidance and influenced Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. (21)

As for how the divinations in the I Ching was modified to Xiangqi, or how it could have affected the birth of a game that was the precursor to Xiangqi remains unknown and contested.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

A final noted about the Western Zhou

The content mentioned above would show the important facts or bits of history related to Bo and perhaps Xiangqi. Some of the work has been mentioned in important books, while other passages have been mentioned but not about Xiangqi. The work presented here has been the efforts by the Webmaster to try to trace every possible hypothesis with regards to the origins of Xiangqi. The Webmaster also hopes that interested historians in the history of Chess will be more informed about the actual Chinese hypotheses or theories regarding the origins of Xiangqi.

In the next article, which would focus on the relevant bits of Xiangqi history in the Spring and Autumn Period, more will be said about Bo, Liubo, and other related and important passages. Indeed, many books or writings on Xiangqi in both Chinese and English have mentioned the various passages from the Spring and Autumn Festival with regards to Confucius, Lie Zi, Mencius, Zhuang Zi et cetera.

Liubo and how to play the game will be tackled in yet another article. For interested readers, the article by my good friend Jean-Louis Cazaux is highly recommended.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

References

1. contributors, Wikipedia. King Mu of Zhou. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 980321284, Sep 25, 2020. [Cited: Oct 10, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=King_Mu_of_Zhou&oldid=980321284.

2. —. Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 975649598, Aug 29, 2020. [Cited: Oct 10, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tale_of_King_Mu,_Son_of_Heaven&oldid=975649598.

3. 维基百科编者. 周穆王. 基百科,自由的百科全書. [線上] 条目版本编号:62226678, 2020年Oct月6日. [引用日期: 2020年Oct月10日.] https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E5%91%A8%E7%A9%86%E7%8E%8B&oldid=62226678.

4. 张, 如安. 中国象棋史. 北京 : 团结出版社, 1998. 7-80130-170-6.

5. Wikisource贡献者. 穆天子傳/卷五. Wikisource,。. [联机] 页面版本ID:1523493, 2018年Dec月25日. [引用日期: 2020年Oct月10日.] R|https://zh.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=%E7%A9%86%E5%A4%A9%E5%AD%90%E5%82%B3/%E5%8D%B7%E4%BA%94&oldid=1523493}-.

6. (战国)不详. Pre-Qin and Han -> Histories -> Mutianzi Zhuan -> 卷五. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [線上] [引用日期: 2019年Nov月7日.] https://ctext.org/mutianzi-zhuan/juan-wu/ens.

7. 李, 松福. 象棋史话. 北京 : 新华书店北京发行所, 1981. 7015.1939.

8. contributors, Wikipedia. Shuowen Jiezi. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] age Version ID: 978571655, Sep 15, 2020. [Cited: Oct 10, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shuowen_Jiezi&oldid=978571655.

9. —. Tang of Shang. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 923369306, Oct 28, 2019. [Cited: Oct 10, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tang_of_Shang&oldid=923369306.

10. 维基百科编者. 中國博弈史. 维基百科,自由的百科全書. [線上] 条目版本编号:22917475, 2012年Sep月23日. [引用日期: 2020年Oct月23日.] https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E4%B8%AD%E5%9C%8B%E5%8D%9A%E5%BC%88%E5%8F%B2&oldid=22917475.

11. (西汉)司马迁. Pre-Qin and Han -> Histories -> Shiji -> Annals -> Annals of Yin. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Jan 4, 2020.] https://ctext.org/shiji/yin-ben-ji/ens#n4567.

12. contributors, Wikipedia. Wu Yi of Shang. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 980299851, Sep 25, 2020. [Cited: Oct 10, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wu_Yi_of_Shang&oldid=980299851.

13. —. Records of the Grand Historian. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 981490571, Oct 2, 2020. [Cited: Oct 14, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Records_of_the_Grand_Historian&oldid=981490571.

14. Wikisource贡献者. 太平御覽 (四庫全書本)/卷0753. Wikisource,。. [Online] 页面版本ID:776280, Oct 26, 2016. [Cited: Feb 15, 2020.] -{R|https://zh.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=%E5%A4%AA%E5%B9%B3%E5%BE%A1%E8%A6%BD_(%E5%9B%9B%E5%BA%AB%E5%85%A8%E6%9B%B8%E6%9C%AC)/%E5%8D%B70753&oldid=776280}-.

15. contributors, Wikipedia. Taiping Yulan. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 951483340, Apr 17, 2020. [Cited: Oct 14, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Taiping_Yulan&oldid=951483340.

16. —. Siku Quanshu. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 963993885, Oct 14, 2020. [Cited: Oct 14, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Siku_Quanshu&oldid=963993885.

17. 陳, 家弘. "大裨聖教"或"牧豬奴戲"?宋代博弈文化研究. 歷史學系研究所, 國立政治大學. 台北 : s.n., 民國102年 (2003). p. 134.

18. Himly, K. The Chinese Game of Chess as Compared with that Practised by Western Nations. Journal of the North-China Brance of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1869 & 1870, New Series No. VI, pp. 105-122.

19. Hooper, David and Whyld, Kenneth. The Oxford Companion to Chess. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1984. Oxford University Press.

20. Needham, Joseph, Wang, Ling and Robinson, Kenneth Girdwood. Science and Civilization in China, Volume IV:1. 6th Printing, 2004. London : Cambridge University Press, 2004. 0521058023.

21. contributors, Wikipedia. I Ching. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 982790408, Oct 10, 2020. [Cited: Oct 14, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=I_Ching&oldid=982790408.

22. —. Zhou dynasty. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 977898361, Sep 11, 2020. [Cited: Sep 29, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Zhou_dynasty&oldid=977898361.

23. —. Spring and Autumn period. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 981242741, Oct 1, 2020. [Cited: Oct 10, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Spring_and_Autumn_period&oldid=981242741.