Origins of Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) 03: King Wu of Zhou Hypothesis

One of the most important hypotheses about the origins of Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) was that King Wu of Zhou (周武王 Zhōu Wǔ Wáng c. c. 1100 BC – c. 1043BC) invented it when he overthrew the cruel King Zhou of Shang (纣王zhòu wáng).

One of the most important hypotheses about the origins of Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) was that King Wu of Zhou (周武王 Zhōu Wǔ Wáng c. c. 1100 BC – c. 1043BC) invented it when he overthrew the cruel King Zhou of Shang (纣王zhòu wáng).

- Hypothesis Number 4: King Wu of Zhou invented Xiangqi when he overthrew King Zhou of Shang.

This hypothesis would be the first of several hypotheses relating to Xiangqi's origins that would have more substance than the previous three mythical hypotheses mentioned in another article. Unfortunately, in the Webmaster's opinion, it is also one of the most overlooked hypotheses because of confusion by the early Western scholars.

This article will briefly examine the hypothesis in detail and exhibit some of the Webmaster's research over the past few years. Only part of the research can be presented here because the Webmaster is still searching for a few documents that have eluded him for the past few years.

A short introduction to King Zhou of Shang, King Wu of Zhou, and the Zhou Dynasty

The Hypothesis of King Wu of Zhou inventing Xiangqi

Mistaken people, books, and events

HJR Murray questions the validity of this hypothesis

Things we can learn or understand from the King Wu of Zhou hypothesis

The Chariot in the Zhou Dynasty

Jiang Taigong, Military Tactics, and Military Strategy

A short introduction to King Zhou of Shang, King Wu of Zhou, and the Zhou Dynasty

King Wu of Zhou may be better known to some as Ji Fa (姬發 jī fā), who founded the Zhou dynasty. The Zhou dynasty was THE LONGEST DYNASTY in China's history, stretching from about 1046 BC – 245 BC.

The Zhou Dynasty succeeded the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BC). (2) The last ruler of the Shang Dynasty was the evil King Zhou of Shang (纣王 zhòu wáng c. 1075-1046BC). The Shang Dynasty was overthrown when King Wu of Zhou defeated King Zhou of Shang at the Battle of Muye. King Wu of Zhou had the help of Jiang Taigong, who will be discussed later. (3)

Short notes: The Shang Dynasty and King Zhou of Shang might also have played a role in the origins of Xiangqi.

1) Liubo, an ancient game believed to be a chess prototype whereby Xiangqi was derived, was thought to have been invented by a minister of the Shang Dynasty. This portion of history would be examined under another separate article discussing Liubo.

2) There is another interesting passage found in the version of Tai Ping Yu Lan that was preserved in Si Ku Quan Shu. While one of the hypotheses that King Wu of Zhou invented Xiangqi, there was mention of his arch-enemy, King Zhou of Shang, being the inventor of Bo. This sub-topic would be presented in another separate article.

3) There was a torture method called the "Cannon Burning Punishment" that was believed to have been invented by King Zhou of Shang invented. The invention has also been attributed to Jie, another earlier Emperor of the Shang. It was mentioned in the English Wikipedia article only recently and was not present in the Wikipedia article when the Webmaster researched a few years ago.

The "Cannon Burning Punishment" was invented to please the sadistic Da Ji (妲己Dá jǐ), King Zhou of Shang's favorite concubine.

Quote from Wikipedia:

"One large hollow bronze cylinder was stuffed with burning charcoal and allowed to burn until red-hot, then prisoners were made to literally hug the cylinder, which resulted in a painful and unsightly death."

The Chinese for the torture is 炮烙 pào luò. It is also one of the EARLIEST MENTION OF THE CANNON WITH THE RADICAL FIRE THAT THE WEBMASTER CAN FIND. FIREPOWDER WOULD ONLY BE INVENTED OVER A THOUSAND YEARS LATER. The identity of the 'cannon' in this torture and its relationship with the Cannon chess-piece remains a mystery as the Webmaster is still researching.

This torture method IS NOT MYTHICAL as it was mentioned in the Records of the Grand Historian. There is a short, perhaps a little bit inaccurate translation that can be found on another website.

《史记·殷本纪》曰:“于是纣乃重刑辟,有炮烙之法。” (5)

"The people murmured, and when the nobles rebelled Zhouxin (another name for King Zhou of Shang) increased the severity of his punishments, instituting the punishment of roasting." (5 页 quote 31)

The Zhou Dynasty would later be fragmented into the Western Zhou (c.1046-771 B.C.) and Eastern Zhou (c. 771-256 BC) Dynasties. The history of the Zhou Dynasty is complicated because part of the territory was later fragmented into several states, giving birth to the Spring and Autumn Period and the Period of the Warring States. The centralized power of the Zhou Dynasty waned as the warring states fought each other, which finally culminated in the State of Qin unifying China to form the Qin Dynasty. (6)

King Wu of Zhou has been deemed as one of the most benevolent and widely celebrated emperors in the history of China. (7)

Click here to return to the top of page.

The Hypothesis of King Wu of Zhou inventing Xiangqi

Regarding Xiangqi, one of the hypotheses suggested that King Wu of Zhou invented Xiangqi to teach his troops the finer details of the strategy.

Zhou Jiasen mentioned this hypothesis in his book and even went so far as to cite a poem from the Book of Odes and Hymns to prove how valuable chariots and horses were during King Wu of Zhou's time.

According to Zhou Jiasen, this was why there were five pawns for each color on the Xiangqi board. Zhou Jiasen gave the date of this possible hypothesis as 1134-1120BC).

The following is the author's translation:

"Xiangqi was created when King Wu of Zhou attacked King Zhou of Shang. According to the military system during King Wu of Zhou's time, five men were grouped together. This would explain why there are five pawns per player in Xiangqi. During King Zhou of Wu's time, the Chariot and horse were most important. There is a verse in the Book of Odes and Hymns: 'as my chariot attacks, my horse shall go too.' (1134 BC to 1120 BC) ".

周家森 《象棋與棋語.象棋源流考》:

“象棋為周武王伐紂時所作,紀武功也,周禮兵制,五人為伍,象棋以兵卒為五,用周制也。按周時戰爭,最重車馬,毛詩所謂 「我車既攻,我馬既同」是也。(西元以前一一三四至一一二〇年) (8 p. 1)

Another modern-day historian, Li Songfu (李松福), also mentioned the same hypothesis. However, according to Li, in King Wu of Zhou's time, soldiers arranged in groups of five with a leader for a six-man unit instead of a five men unit. Like Zhou Jiasen, Li Songfu used the arrangement of the men to explain why there are five pawns for each player at the beginning of the game of Xiangqi (9 p. 11).

The origins for the hypothesis was based mainly on the Wu Za Zu (《五雜俎》 wǔ zá zǔ), which was written by a Ming Dynasty scholar called Xie Zhaozhe (谢肇淛 xiè zhào zhè, 1567 AD – 1654 AD). The following is the author's translation of relevant parts of the passage.

Wu Za Zu, Second Part of the Chapter on Ren:

"Xiang Xi was believed to have been created when King Wu of Zhou ousted King Zhou of Shang; if not, it should have been around during the Period of the Warring States when the Chariot was an important part of doing battle. When soldiers entered enemy territory, there was no turning back. It would become a kill or be killed situation.

The options are many, and it is similar to Weiqi. Infinite are the possibilities during to and fro attacks and defense …… Xiangqi is less complicated than Weiqi …to have the initiative and not be controlled by the enemy."

《五雜俎。人部二》

" 象戲,相傳為武王伐紂時作,即不然,亦戰國兵家者流,蓋時猶重車戰也。兵卒過界,有進無退,正是沉船破釜之意。其機會變幻,雖視圍棋稍約,而攻守救應之妙,亦有千變萬化,不可言者,金鵬變勢略備矣。而尚有未盡者,蓋著書之人,原非神手也。象戲視圍棋較易者,道有限而算易窮也。至其棄小圖大,制人而不制於人,則一而已。" (10)

German historian Peter Banaschak's translation was:

"Xiangqi, according to tradition made by King Wu of Zhou in the time of his final campaigns against Shang; if that is not so, at least it became popular among military personnel in the time of the contending realms, as in this time chariot warfare was still important." (11)

Note: Mr. Banaschak only had the first portion of Xie Zhaozhe's text "象棋相傳為武王伐紂時作即不然亦戰國兵家者流蓋時猶重車戰也" in his article and did not have the rest of the passage, and the article was given in traditional Chinese.

Xie Zhaozhe clearly stated that Xiangqi was believed to have been created by King Wu of Zhou or that it was already prevalent in the Period of the Warring States. To prevent people from mistaking Xiangqi for Weiqi, which was also very popular back then, Xie also clearly stated that Xiangqi and Weiqi were entirely different entities. Xie also the two games, saying both had nearly infinite possibilities, but that Xiangqi was the simpler of the two. (8 p. 6)

Later, historians would often suggest that Xiangqi was mistaken for Weiqi, but Xie Zhaozhe's passage would quell this argument.

Click here to return to the top of page.

Mistaken people, books, and events

King Wu of Zhou has been translated as 'Wu Wang' in some early literature on the topic, including HJR Murray. This name is NOT TO BE MISTAKEN WITH EMPEROR WU OF THE NORTHERN ZHOU DYNASTY, WHICH EXISTED ABOUT 1500 YEARS LATER. The two people are different, and both of them have been implicated in the history of Xiangqi.

King Wu of Zhou has been translated as 'Wu Wang' in some early literature on the topic, including HJR Murray. This name is NOT TO BE MISTAKEN WITH EMPEROR WU OF THE NORTHERN ZHOU DYNASTY, WHICH EXISTED ABOUT 1500 YEARS LATER. The two people are different, and both of them have been implicated in the history of Xiangqi.

For the Westerner, the 'Zhou' in King Wu of Zhou and King Zhou of Shang are different Chinese characters ('周' zhōu and '肘' zhǒu respectively) which happen to have similar Hanyu Pinyin. The intonations are different, though.

Another important character in Chinese history, that the reader might be mistaken, is Emperor Wu of the Northern Zhou Dynasty, who could also be called Zhou Wudi (周武帝 zhōu wǔ dì) in Chinese. These three people are all different. Indeed, King Wu of Zhou and Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou have been mistaken in the past. The fact that the names seem so similar has caused some confusion to Western scholars like HJR Murray.

IN FACT, MURRAY CAME UP WITH AN EXPLANATION DENOUNCE SOME OF THE ANCIENT ORIGINS OF XIANGQI STEMMING FROM HIS MISINTERPRETATION OF THE ANCIENT TEXTS.

"Wu-Ti adopted the name of Chou from the older dynasty of that name (1135-256 BC). It happens that the first emperor of the older house was name Wu-Wang (1135-1115 BC), and this had led to confusion. First, Wu-Ti's siang-k'i is identified as Chess, next Wu-Ti is interchanged with Wu-Wang, and in this way, the origin of the usual statements claiming a high antiquity for Chinese Chess is obtained. The more reliable Chinese historians notice this and warn their readers of the confusion. Thus the Ko chi King Yuan, 'the Mirror of investigations' into the Origins of Things,' quoting from the Shi-Wu-chi-yuan the passage, 'Yung Mong Chou said to Meng Ch'ang-chun (D. B.C 279): Sir, when you have leisure, play siang-Ki,' adds the pertinent question, 'But was siang-k'I known at the time of the Warring Kingdoms (B.C 484-221)?' and the encyclopaedia T'ai Ping Yu Lan discusses the point at great length…." (12 pp. 122-123)

A few notes to discuss HJR Murray's passage:

a) There are many games in ancient China whereby the collective noun has been given as Chess.

b) 'Wu-Ti's siang-k'I is identified as chess' à correct, as 'chess' would be used as a general term. It would suggest an ancient prototype that was invented by Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou.

c) 'next Wu-Ti is interchanged with Wu-Wang' à NO! The names are have caused confusion in the past, and the Webmaster has indeed found errors in scribing in the past, BUT THE TWO PEOPLE ARE DIFFERENT. Proof can be found in the Records of the Grand Historian. King Wu of Zhou was mentioned in the Records, which was WRITTEN CENTURIES BEFORE EMPEROR WU OF NORTHERN ZHOU WAS BORN. The Book of Chou was a history of the Northern Zhou Dynasty wrote centuries after the Records of the Grand Historian. (Note: The Book of Chou 《周书》Zhōu shū was used and quoted by Murray to introduce the hypothesis that Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou invented Xiangqi should be Book of Zhou if modern-Hanyu Pinyin were used.)

To further complicate things, there is another book, called The Lost Book of Zhou (《逸周书》yì Zhōu shū) (12) which would discuss the history of the Zhou Dynasty (not the Northern Zhou Dynasty). 《逸周书》 was sometimes simply given as 《周书》 in some of the earlier texts like Shuo Yuan!

Given below is a passage from Shuo Yuan which uses 《周书》 to refer to 《逸周书》 and NOT the Book of Zhou, which was a history mentioning Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou:

公乘不仁曰: "《周书》曰:‘前车覆,后车戒。' (14 页 passage 12)

And, as fate would have it, one of the earliest mentions of the phrase 'Xiangqi' was given slightly later in the Shuo Yuan, a few paragraphs from the quote mentioned immediately above:

"燕则斗象棋而舞郑女" (14 页 passage 12)

The Webmaster suspects that Murray might also have mistaken the books too. All three books can be easily accessed from the links given in the reference page below.

d) 'and in this way, the origin of the usual statements claiming a high antiquity for Chinese chess is obtained' à NO! WRONG! The Webmaster has NEVER READ ANYTHING ALONG THOSE LINES IN THE CHINESE BOOKS. Murray's passage was the first-ever passage that the Webmaster has ever read along these lines.

e) 'The more reliable Chinese historians notice this and warn their readers of the confusion.' à no names were mentioned that could allow the Webmaster to check the facts.

f) "Thus the Ko chi King Yuan, 'the Mirror of investigations' into the Origins of Things,' quoting from the Shi-Wu-chi-yuan the passage, 'Yung Mong Chou said to Meng Ch'ang-chun (D. B.C 279): Sir, when you have leisure, play siang-Ki,' adds the pertinent question, 'But was siang-k'I known at the time of the Warring Kingdoms (B.C 484-221)?" -à Another very obscure passage from Murray. The Webmaster has found some interesting 'inadequacies' in Murray's description. Murray is believed to have quoted K. Himly, one of the first to have introduced the West's passage back in the 19th century. Due to the scope of this article, this section would be discussed in another article. It would suffice to say that the Webmaster believes that there was another fatal mistake in translation.

Click here to return to the top of page.

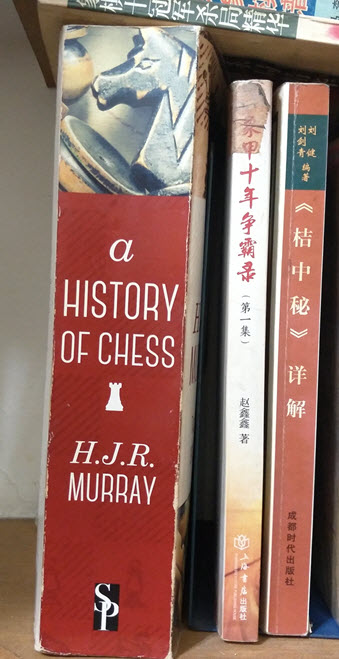

HJR Murray questions the validity of this hypothesis

After suggesting that Chinese history had mistaken King Wu of Zhou and Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou for each other, Murray finally discussed the hypothesis of King Wu of Zhou inventing Xiangqi.

After suggesting that Chinese history had mistaken King Wu of Zhou and Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou for each other, Murray finally discussed the hypothesis of King Wu of Zhou inventing Xiangqi.

Murray also mentioned Wu Za Zu, but he used Wu-tsa-tsu, which was a Romanized system. Unfortunately, there was another inaccurate translation.

HJR Murray stated that:

"The Wu-tsa-tsu says the tradition that sian-hi ( should be Xiang Xi 象戏, xiàng xì, one of the ancient names of Xiangqi) was invented by Wu Wang at the time of the war of the Chou IS CONTRARY TO FACT. The Chariot was still esteemed in warfare at the time of the Warring Kingdoms. The ability of the soldiers to cross the boundary, and to advance, but not to retreat, signifies that the boat must be sunk, and the axe broken. Although opportunities and chances are somewhat restricted in Wei-k'I, there are countless opportunities for the practice of strategy in the attack, in defense and in alliance."

HJR Murray later concluded that:

"This passage is very obscure, but it appears to argue that Chess represents a type of warfare that was inconsistent with its existence as early as the third c. B.C."

It was a dreadful mistake in translation. The intended meaning in Xie's passage should have been (using HJR Murray's words):

"… Xiang Xi was believed to have been created during the time when King Wu of Zhou ousted King Zhou of Shang; IF NOT (or OTHERWISE can also be used), it should have been around during the period of the Warring States, when the Chariot was an important part of war."

Peter Banaschak's translation would give further proof of the mistake in interpretation by HJR Murray.

The linguistics are clear, and there is no ambiguity in the original passage. HJR Murray has the author's respect for having mounted on the gargantuan task of trying to write about the history of Chess, but it was unfortunate that he did not know Chinese. It must also have been tough in his time to have managed to get hold of ancient Chinese writings and to have a decent translator help him with his work.

Perhaps, if he had learned Chinese, or had a correct translation, it might have changed his views on the origins of Xiangqi or Chess for that matter. (12 p. 123)

Another thing to note was that Murray was perhaps blurred by this time that he suggested that 'with its existence as early as the third c. B.c', which would reference 'Yung Mong Chou said to Meng Ch'ang-chun (D. B.C 279). By this point in his chapter, Murray had already discounted the King Wu of Zhou hypothesis, as King Wu of Chou lived approximately eight centuries earlier.

The Webmaster recalls a sense of bewilderment when he first read Murray's passage in these two pages a few years ago. After all, there were so many quotes and seemingly logical explanations that were presented a smooth flow of logic.

It seemed to make sense, BUT it was disturbingly different from what the Chinese historians had presented in the ancient texts. If you were to break each claim down one by one, there would seem to be many inaccuracies in Murray's work.

Speaking of translators, the great translator, James Legge (1815 – 1897 AD), also mentioned Xiangqi as being:

"ascribed to the first emperor of the Chow dynasty (B.C 1122)." (15 pp. 245-246)

James Legge's writings will be covered in more detail in another article.

Click here to return to the top of page.

Things we can learn or understand from the King Wu of Zhou hypothesis

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, the Webmaster believes that the King Wu of Zhou hypothesis has been overly ignored when discussing the origins of Xiangqi. Admittedly, ascribing the invention of a game as profound as Xiangqi to a king that lived over three thousand years ago would raise many doubts. However, the hypothesis should not be completely ignored.

Early research, especially by Western scholars, focused on specific texts and passages that contained Xiangqi. The Webmaster has tried to search for clues to the origins of Xiangqi in another light.

Instead of focusing on passages from the ancient texts, which are still very important, the Webmaster has tried to search for origins of the individual elements.

Chariots, Elephants, Horses, et cetera could not have appeared out of anywhere. What about the elements of military strategy which permeate Xiangqi? It would be next to impossible to try to invent a palace and place it on the board. Elements of the culture of the Chinese could be seen everywhere in the game. So, it is possible that the game pieces, the chessboard, the river, the palace could have origins rooted in Chinese culture or history? These were some of the questions that the Webmaster asked himself as he embarked on his own journey to search for Xiangqi's origins.

So, what have we learned so far from the King Wu of Zhou hypothesis?

- From Xie Zhaozhe's writings and the various translations given above, we see mention of five soldiers as a unit in ancient warfare, which would correspond to the number of pawns in modern-day Xiangqi.

- The Webmaster would also like to point out the fact that the soldiers can only advance and not retreat after crossing the river in the boat. Peter Banaschak did not mention this. One could argue that Xiangqi was already well-established by Xie Zhaozhe's time (Ming Dynasty) and that it could have well been Xie Zhaozhe's interpretation or opinion.

- The Chariot is mentioned and is also an integral part of Xiangqi.

- Xiangqi, or rather, an ancient prototype of Xiangqi, was different from Weiqi. They were not the same entity. Indeed, in future articles, the Webmaster will show proof of different early Western historians mistaking Xiangqi or its ancient prototypes for Weiqi and other games of old like Chapur, Prasaka, Tan Qi, et cetera.

But are these the only things that the King Wu of Zhou hypothesis can provide? The Webmaster believes that there is so much more to learn.

- As mentioned earlier, King Zhou of Shang and the Shang Dynasty seemed to have something to do with the Games of Bo and Liubo (to be discussed in another article).

- The literal 'roasting' of people with the "Cannon Burning Punishment" by King Wu of Shang…could it have anything to do with the Cannon piece in Xiangqi? So far, the Webmaster has not been able to find any link.

- The Mingtang (明堂 míng táng) was established during the Zhou Dynasty, where there were important rites. It was part of the Mandate of Heaven, which was presented as a religious compact between the Zhou people and the heavenly gods. The Mingtang was a building or architecture with NINE ROOMS. And the Mingtang had something to do with the Luo Shu, as mentioned in the section on Fuxi in the article on the hypotheses of Xiangqi with mythical origins. The Luo Shu could be turned into a magical square that was cited by Pavle Bidev and also partly by Professor Joseph Needham to ascribing the origins of Xiangqi to China.

- King Wu of Zhou could not have defeated King Zhou of Shang had it not been for the help of Jiang Ziya who might be better known as Jiang Taigong who will be discussed later.

Click here to return to the top of page.

The Chariot in the Zhou Dynasty

The Chariot was specially mentioned in the Xie Zhaozhe's passage, which stated:

"… during the Period of the Warring States when the chariot was an important part of doing battle."

There were several types of chariots during the Period of the Warring States. What has this to do with Xiangqi?

One of the earliest archeological findings of the Xiangqi chariot piece depicted a wartime supply chariot. Traditionally, chariots have been used to fight in wars and act as supply vehicles known as Zi Che (辎车 Zǐ Chē) in Chinese.

Ralph Sawyer mentioned in his book that:

"The Chariot functioned as the basic fighting unit during the late Shang, Western Chou, and Spring and Autumn (722 – 481 B.C) periods; it remained important until well into the Warring States (403-221), when it was gradually supplanted by large infantry masses, and eventually, during the third century B.C, began to be supplemented by the cavalry…

However, twentieth-century archaeological discoveries, supplemented by textual research, indicate that the Chariot, rather than being an indigenous development, did not reach China from Central Asia until the middle of the Shang dynasty – approximately 1300 to 1200 B.C. Initially, the use of Chariot was probably confined to ceremonies and transportation and only gradually was expanded to the hunt and eventually to warfare." (16 p. 5)

What was interesting to the Webmaster was Ralph Sawyer's passage was 'confined to ceremonies.' It would seem that the Chariot might have had a role in the various ceremonies that were part of the 'Mandate of Heaven.' However, at this point, the Webmaster has not been able to shed more light. A possible hunch that the Webmaster has been trying to pursue would be the Chariot and the Mingtang.

As for the hypothesis that King Wu of Zhou created Xiangqi, there have not been any archeological findings to back it up to the author's knowledge.

It is one of the most baffling mysteries. One of the most commonly used arguments by Western historians to prove that Xiangqi or any prototype could NOT have existed so early in history. Perhaps the original game was made of wooden pieces that disintegrated over time. Nobody knows.

Click here to return to the top of page.

Jiang Taigong, Military Tactics, and Military Strategy

It would be noteworthy to mention that one of King Wu of Zhou's most trusted ministers was the legendary Jiang Tai Gong (姜太公 jiāng tài gōng ?-?), who was well known for his patience. Jiang Taigong is known by many other names like Jiang Ziya (姜子牙 Jiāng Zǐyá), Lü Shang (呂尚 Lǚ Shàng), et cetera.

While Confucius was recognized as the Great Sage for many disciplines including philosophy, politics, et cetera, Jiang was revered as the Sage of Military Affairs.

Legend has it that he once went fishing with a line devoid of a fishhook on his fishing rod, patiently waiting for willing fish to take the bait. This legend would later give rise to the saying When Jiang Taigong went fishing, the willing would take the bait (姜太公钓鱼,愿者上钩 Jiāng Tàigōng diào yú yuàn zhě shàng gōu).

It was also during one of his fishing trips that he met King Wen of Zhou (周文王Zhōu Wén Wáng, c. 1125-1046 BC), who was the father of King Wu of Zhou mentioned above. Jiang Taigong would serve as the military advisor to both kings and be instrumental in toppling the Shang Dynasty to establish the Zhou Dynasty.

Click here to return to the top of page.

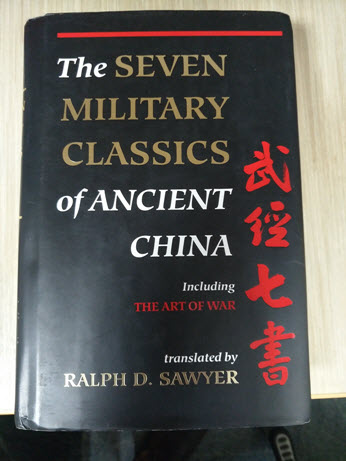

The Six Secret Teachings

The Westerner may be familiar with Sun Zi and his Sun Zi's Art of War, but Jiang lived much earlier than Sun Zi. He had also written Six Secret Teachings (《六韬》 liù tāo), which was also much earlier than Sun Zi's Art of War. Together with five other ancient manuscripts, these seven works formed the Seven Military Classics of Ancient China (《武经七书》 wǔ jīng qī shū). There are many related terms to Jiang Tai Gong in Xiangqi terminology. Jiang Tai Gong and King Wu of Zhou will be mentioned many times in this book. (17) (18) (19)

The Westerner may be familiar with Sun Zi and his Sun Zi's Art of War, but Jiang lived much earlier than Sun Zi. He had also written Six Secret Teachings (《六韬》 liù tāo), which was also much earlier than Sun Zi's Art of War. Together with five other ancient manuscripts, these seven works formed the Seven Military Classics of Ancient China (《武经七书》 wǔ jīng qī shū). There are many related terms to Jiang Tai Gong in Xiangqi terminology. Jiang Tai Gong and King Wu of Zhou will be mentioned many times in this book. (17) (18) (19)

The Webmaster has mentioned Jiang Taigong and his Six Secret Teachings because many book passages could be related to strategic planning and tactics in Xiangqi.

For example, one of the Webmaster's favorite passage would be from the Chapter on Tiger Secret Teaching:

"The T'ai Kung said: "Every single day have the vanguard go forth and instigate skirmishes with them in order to psychologically wear them out. Have our older and weaker soldiers drag brushwood to stir up the dust, beat the drums and shout, and move back and forth – some going to the left, some to the right, never getting closer than a hundred paces from the enemy. The general will certainly become fatigued, and their troops will become fearful. In this situation, the enemy will not dare come forward. Then our advancing troops will [unexpectedly] not stop, some [continuing forward] to attack their interior, others the exterior." (16 p. 83)

The T'ai Kung said: "Now the rule for commanding an army is always to first dispatch scouts far forward so that when you are to hundred li from the enemy, you will already know their location. If the strategic configuration of the terrain is not advantageous, then use the Martial Attack chariots to form a mobile rampart and advance…" (16 p. 86)

There was also mention of battle formations in the Six Secret Teachings. Formations, or tactical combinations as International Chess players might be better related to, are Xiangqi's soul. Therefore, in the Webmaster's opinion, although it is very unlikely that the modern-day form of Xiangqi had existed then, the conditions were favorable for the birth of a game, which could be the ancient prototype of Xiangqi.

Click here to return to the top of page.

Similar history in West

Interestingly, the concept of formations would not be alien to the West.

The Greeks were known to have had the phalanx as an attacking formation when they did battle. There are records of such usage as early as c. 2400 BC. (20)

The Bible mentioned that the Israelites moved camp in an orderly formation when Moses ordered it. Please refer to Numbers 10:11-25. Moses was alleged to have lived around the 14th -13th century BCE.

There were also many instances of tactics used in warfare in the West.

Joshua was known to have attacked enemies in greater numbers with clever tactics. One of the battles that the Webmaster was particularly impressed with was the Fall of Ai. See Bible, Joshua 8: 9-23.

Samson, who was one of the Judges of Israel, was also known for ingenious ways of attacking the enemy. In Judges 15: 3-5, the following was written:

Judges 15:4-5 KJV

4. And Samson went and caught three hundred foxes, and took firebrands, and turned tail to tail, and put a firebrand in the midst between two tails, firebrands: or, torches

5. And when he had set the brands on fire, he let them go into the standing corn of the Philistines, and burnt up both the shocks and the standing corn, with the vineyards and olives.

There was a similar method of attack in China where bulls were used instead of foxes. Sharp knives were also tied to the horns of the bulls to increase their destructive power. Tian Dan (田单 tián dān ? - ?) was known for a military tactic called Fiery Bull Attack (火牛阵huǒ niú zhèn ). Wikipedia had translated the method of attack as 'Fire Cattle Columns' in about 2nd century B.C. (21)

Therefore, there were examples using formations and tactics in warfare in both the East and West. In China, Jiang Taigong's Six Secret Teachings would mark the start of studying military strategy as a subject of his own.

Click here to return to the top of page.

Afterthoughts

It would be extremely hard to suggest that Xiangqi had already been invented during the 12th Century BCE. However, it does seem that the environment or the conditions were already ripe for the invention of a prototype of Xiangqi.

The actual relationship, if any, between the Mingtang, magic squares, and possibly the palace on the Xiangqi board remains an elusive topic for the Webmaster.

As mentioned earlier, the Zhou Dynasty, King Wu of Zhou, Jiang Taigong, King Wu of Shang, et cetera may all have something to do with the origins of Xiangqi. Unfortunately, there has been little mention of this section in Western literature.

Click here to return to the top of page.

References

1. (明)王圻. 線上圖書館 -> 三才圖會 -> 三才圖會 52/289. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Feb 26, 2020.] https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=103549&page=52.

2. contributors, Wikipedia. Shang dynasty. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 980826554, Sep 28, 2020. [Cited: Sep 29, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shang_dynasty&oldid=980826554.

3. —. King Zhou of Shang. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 980307385, Sep 25, 2020. [Cited: Sep 29, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=King_Zhou_of_Shang&oldid=980307385.

4. 维基百科编者. 炮烙. 维基百科,自由的百科全書. [联机] 条目版本编号:55110395, 2019年Jul月07日. [引用日期: 2020年Oct月1日.] https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E7%82%AE%E7%83%99&oldid=55110395.

5. (西汉)司马迁. Pre-Qin and Han -> Histories -> Shiji -> Annals -> Annals of Yin. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Jan 4, 2020.] https://ctext.org/shiji/yin-ben-ji/ens#n4567.

6. contributors, Wikipedia. Zhou dynasty. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 977898361, Sep 11, 2020. [Cited: Sep 29, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Zhou_dynasty&oldid=977898361.

7. —. King Wu of Zhou. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Oct 13, 2019. [Cited: Nov 17, 2019.] Page Version ID: 921086183. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=King_Wu_of_Zhou&oldid=921086183.

8. 周, 家森. 象棋与棋话 第三版. s.l. : 世界书局印行, 1947, 民国36年. No ISBN.

9. 李, 松福. 象棋史話. 北京 : 人民体育出版社, 1981.7. 7015.1939.

10. (明)谢肇淛. Wiki -> 五杂俎 -> ●卷六·人部二. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Dec 15, 2019.] https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&chapter=470591&remap=gb.

11. Banaschak, Peter. FACTS ON THE ORIGIN OF CHINESE CHESS (XIANGQI 象棋). http://www.banaschak.net/. [Online] No date given. [Cited: Mar 15, 2020.]

12. Murray, HJR. A History of Chess ( 1913 Orginal Edition). New York : Skyhorse Publishing, 2012. reprint. 978-1-63220-293-2.

13. 《逸周书 - Lost Book of Zhou》. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Sep 29, 2020.] https://ctext.org/lost-book-of-zhou/ens.

14. Pre-Qin and Han -> Confucianism -> Shuo Yuan -> 善说. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Sep 29, 2020.] https://ctext.org/shuo-yuan/shan-shuo/ens?searchu=%E5%88%99%E6%96%97%E8%B1%A1%E6%A3%8B&searchmode=showall.

15. Legge, James. The Chinese Classics: Vol. 1. The Life and Teachings of Confucius. London : N. Trubner & Co., 1869.

16. Sawyer, Ralph D. and Sawyer, Mei-chun. The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China. Boulder : s.n., 1993. 978-0-465-00304-4.

17. 维基百科编者. 太公望. 维基百科,自由的百科全書. [Online] Oct 15, 2019. [Cited: Oct 31, 2019.] https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E5%A4%AA%E5%85%AC%E6%9C%9B&oldid=56487988. 目版本编号:56487988.

18. —. 周文王. 维基百科,自由的百科全書. [Online] Oct 10, 2019. [Cited: Nov 17, 2019.] 条目版本编号:56684098. https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E5%91%A8%E6%96%87%E7%8E%8B&oldid=56684098.

19. contributors, Wikipedia. King Wen of Zhou. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Oct 9, 2019. [Cited: Nov 16, 2019.] Page Version ID: 920455692. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=King_Wen_of_Zhou&oldid=920455692.

20. —. Phalanx. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 977368994, Sep 8, 2020. [Cited: Sep 30, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Phalanx&oldid=977368994.

21. —. Tian Dan. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 928157270, Nov 27, 2019. [Cited: Sep 30, 2020.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tian_Dan&oldid=928157270.